|

Is Australia obligated to maintain Double jeopardy?

The newspaper The Australian reported on the 11th February 2003 that the New South Wales Bar Association president, Bret Walker, declared that Australia would be in breach of its obligations under the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights if it were to abolish or modify the law known as Double jeopardy.

This ‘obligation’ certainly did not turn out to be an impediment to the Blair UK government recently abolishing the law in certain circumstances, perhaps because they were not willing to give the ICCPR as much relevance as others in our community would like it to possess.

The obligations of the government under the ICCPR may well be to promote certain concepts in circumstances where the public were otherwise not interested. However it is quite another thing to be obligated to promote concepts where the public are specifically opposed. The very nature of Australia being a democracy and a sovereign state means that the Australian people through their directly elected representatives in Parliament have complete discretion to institute whatever laws they may so wish (subject to the Constitution).

We can not have legislation ‘through the back door’ where parliamentarians may pass vague ‘feel good’ job lot commitments to human rights in lofty idealistic worded ratifications one day, and then later claim that more specific legislation must be passed (or opposed) as it has been mentioned in the earlier parliamentary assent.

The people’s representatives in Parliament must decide whether or not to pass a bill generally only on the merits of said bill. They may be compelled to pass a bill, despite their own misgivings, if they have promised to do such to their constituents, because it is to their constituents that they owe their allegiance, but they do not and certainly must not feel allegiance to any other extrinsic commitment, overseas body or international covenant.

Was the premise of the movie Double Jeopardy correct?

Even though the law of Double jeopardy grants one, in certain circumstances, immunity from prosecution for crimes, such as murder, already committed, the question is often asked whether it can also grant immunity in similar circumstances to be able to commit such crimes.

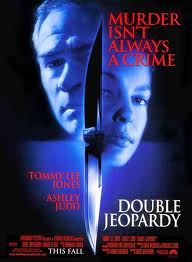

Since 1999 what has instigated such debate is the release of the crime drama “Double Jeopardy” staring Ashley Judd and Tommy Lee Jones. The plot of this fictional thriller is that the Ashley Judd character has been tried and convicted, through due process of law, for the murder of her husband, only to find out later on that her husband is not in fact dead, but orchestrated the whole event so as to claim his life insurance.

She is then informed by a cell mate that, by law, she can never be prosecuted again for that crime, and has in effect, carte blanche to hunt down and kill her husband should the opportunity arise.

[This is not the first film to utilize this questionable aspect of our law to enhance the interest of its plot. In the above eponymous film, the hero, played by Ashley Judd, although threatening to kill the villain while declaring she has immunity, eventually dispatches him in self-defence. No such coyness from the hero in a 1924 American film, where he does hunt down and kill the villain, knowing that his previous conviction, albeit false, for the said person’s murder, will, and does, afford him immunity at any future arraignment. And to emphasis the point for the audience, the name of that early silent movie: It Is the Law.]

As this manifestation of the law would bring ridicule to our judicial system many people who support double jeopardy have argued that the legal premise of this top grossing film is simply false and in real life no such situation of prospective immunity could legally occur.

No less a figure than celebrity defence lawyer and Harvard Law Professor Alan Dershowitz has said that in the film’s situation the double jeopardy defence “…wouldn’t work at all.” Speaking on the NBC Today Show with host Katie Couric he continued “It has to be the same transaction. The same event. It even has to be in the same state…

So the guy who was the legal adviser to this film missed my class on double jeopardy, I think.”

He is certainly not alone in his beliefs. Other sources, in referring to the premise of the eponymous film, have stated

“it wasn't the same offense. It was a different crime — different date, different set of facts”2

and

“Not so in real life: a crime, for double jeopardy purposes, consists of a specific set of facts”3.

Of course this leads one to ask where it actually states in law that to be a criminal offense, an incident must have a complete set of identifiable associated facts.

In response, specific legislation or articles of constitutions are never quoted.

However a common answer to this question is to refer to a criminal arraignment whereby an accused is charged that on a certain day at a certain place he did proceed to commit a certain act whereby uninvited harm was caused to another party or parties.

This is quite true, but those who wish that there are no eccentricities with the law of autrefois acquit, might be confusing common legal court procedure with what is actually mandatory law. That a procedure regularly happens in court does not mean that, by law, it has to happen.

Certain offences definitely have to have associated times simply because the nature of the crime is that they can be repeated. The crime of shoplifting from a supermarket today can be repeated with another crime of shoplifting from the same supermarket tomorrow. Similarly the crime of trespassing must possess the requisite geographical location.

However where these factors are not relevant, it seems spurious to claim that they must be included in the court charge docket. If one is accused of completely destroying the famous Da Vinci painting Mona Lisa, is it really that relevant as to when and where it was done if other evidence tends to prove beyond doubt that it was done and the accused was responsible?

In a hypothetical example relating to murder, suppose a billionaire and his young nephew, the heir to his fortune, go on a travelling six month European holiday. When the young man returns alone and is asked where his uncle is, he casually tells the authorities he and his uncle had an argument approximately six weeks previously, although he forgets the exact date, and the uncle said he was going back home alone. The suspicious police tap the nephew’s phone and eventually tape a confession of him murdering his uncle even though he fails to detail when and where he did it. Considering the authorities have motive, opportunity and a confession it would be preposterous to claim that no prosecution could proceed because the time and place of the murder are unknown.

There used to be an urban myth that if one wanted to get away with murder all the perpetrator had to do was dispose of body such that no trace of it could be found. Thus, because there is no body, it can not (allegedly) be declared that the victim is even dead. There is not and never was any law that stated that. There used to be an urban myth that if one wanted to get away with murder all the perpetrator had to do was dispose of body such that no trace of it could be found. Thus, because there is no body, it can not (allegedly) be declared that the victim is even dead. There is not and never was any law that stated that.

Similarly there is simply no such law that states that to be an offense, an action must be time, date and location stamped. Murder is an absolute, finite act. You cannot part do it and you cannot repeat it. If it can be proved to have been done then when and where it was done is simply irrelevant.

Defenders of the Double jeopardy law become embarrassed when bizarre hypothetical, but unfortunately legally correct situations become publicised in top grossing movies. As a defence they use spurious arguments to claim that in real life it could not happen: arguments that don’t stand up to analysis. If people in the legal profession wish to defend this very questionable law known as autrefois acquit, then they must be prepared to accept both the seemingly unjust as well as the bizarre situations that hypothetically can travel with it. They should have the honesty of their convictions and not shy from the manifestations of the "principles" they advocate.

1. Greg Craven, Conversations with the Constitution, University of NSW, Sydney, 2004 p.165

2. Lawyer Rohn Robbins writing for the Colorado newspaper, the Vail Daily.

3. Writer David Bricker of the Q&A column ‘The Straight Dope” from The Chicago Reader.

|